A Coronal Mass Ejection (or CME) is one of the most spectacular phenomena produced by the Sun. In a nutshell, a CME is a cloud of gas weighing as much as Mount Everest, stretching 10 million km across, and travelling at up to 8 million kilometers an hour! It is not surprising that when a CME hits the Earth it can have a profound effect. This is why they are sometimes called Solar Storms.

A CME is best observed using an instrument called a coronagraph which simulates a solar eclipse by blocking out the main disk of the Sun. This brings the Sun's corona out into sharp relief. One way to picture this is by trying to imagine the light of a match in the bright glare of a car's headlight: block out the headlight with your hand or a book and the match becomes quite visible. This is how a coronagraph works. When the CME occurs, a large mass of ionized gas (or plasma) is ejected and we see it as a spectacular eruption.

| |

The movie shown here from the LASCO instrument on board the SOHO spacecraft shows several large CMEs, which disrupt a significant portion of the solar atmosphere. The random white spots and streaks in the movie are cosmic ray hits on the detector. Cosmic rays are charged particles that continually fly through the Solar System and are believed to come from a variety of energetic sources distributed around the Galaxy and occasionally from the Sun.

|

|

Coronal mass ejections occur at a rate of a few times a week to several times per day depending on the activity of the Sun. The sheer size of these phenomena mean that the Earth is going to be in their way from time to time. When that happens the Earth's atmosphere responds in a number of ways. Fortunately, the atmosphere and magnetic field of the Earth protect us from most of the harmful effects of the coronal mass ejection. However, some energetic particles do make it through to the north or south polar regions, creating the aurora.

Not all coronal mass ejections look the same:

|

|

|

Be aware that the colors used to represent these CMEs are artificial and have no meaning of their own. The important differences are seen in the different shapes of the CMEs shown here. The dynamic behavior of CMEs can also be extremely varied:

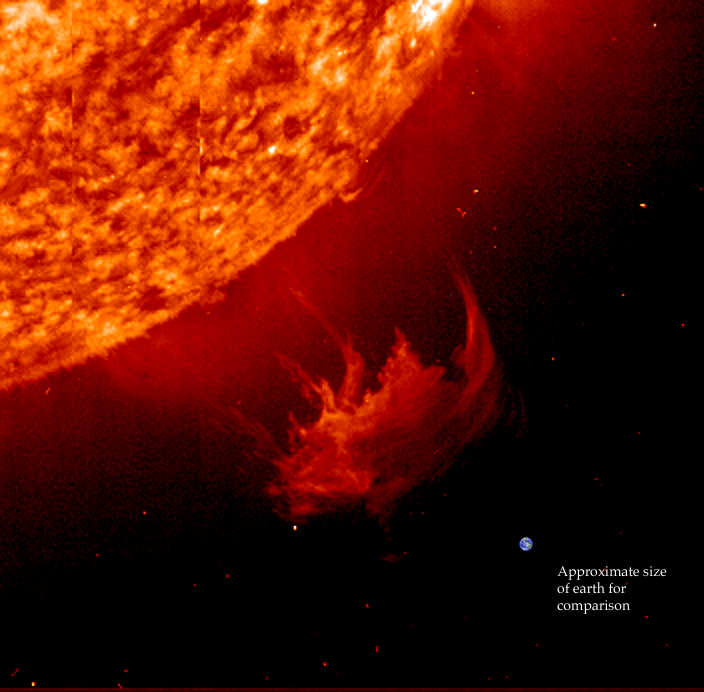

Coronal mass ejections were once thought to be initiated by solar flares. Although some are accompanied by flares, it is now known that most CMEs are associated with a phenomenon called the erupting prominence. The best way to describe an erupting prominence is to show you one.

|

An erupting prominence observed in the Helium 304 channel of the Extreme ultraviolet Imaging Telescope on board the SOHO spacecraft on 6 March 1999. |

|

Another erupting prominence observed, this time, in the Hydrogen alpha line by the Big Bear Solar Observatory on 23 January 1995. This is a full disk movie which illustrates the enormous scale of these events. |

|

|

| The beauty of the various manifestations of eruptive prominences and CMEs only adds to their fascination. If we can come to understand the processes which govern these phenomena we will be a long way towards being able to predict their occurrence. |

Back to Today's Topic