Solstice at Palenque, Chiapas

By Alonso Mendez, Cultural Astronomer

One of the most famous passages in Sophocles’s classic Oedipus Tyrannous is the test that the mythical hero faces with the great Sphinx of Thebes. This beast, that combined the features of a lion and woman, would riddle its beleaguered victims and if its questions were not answered correctly, the poor souls were devoured. The question that was posed to our hero was: “Which animal walks on four legs at the dawn, two legs in the mid-day and three legs at dusk”? The correct answer, and of course our hero’s response, was man; thus allowing Oedipus his safe passage and the death of the Sphinx. This question summarizes in a metaphorical way the life of man as the passage of the Sun through the sky. Another equally poetic metaphor compares the life of humans to the seasons, where life at birth is compared to springtime, the midlife to mid-summer, and finally, old age to the days of winter. A relationship between humans, the Cosmos and time as expressed by the movement of the Sun from day to day as well as its yearly course have always been an essential part of the description of the human experience.

At Palenque, the famous Classic Maya site in the southern state of Chiapas, a similar poetic statement is replayed year after year in the written history as well as in the art and architecture of the site. This site which saw its apogee during the mid to late 7th century, found its maximum height of expression during the rule of the famed K’inich Ja’nab Pakal. At Palenque where the rule of Divine Kingship was at its peak, rulers such as Pakal wielded great power, enough evidently, to bring together the resources and manpower to build some of the most impressive temples seen in the pre-Columbian world. No mean task, as the environment of the tropical lowland forests was a difficult and challenging place to raise a civilization.

Divine rulers depended on their astronomical knowledge to predict the important solar stations such as the solstices, equinox, zenith and nadir passages. By associating their own lives to the movement of the Sun, rulers were able to project the illusion that they were the human presence of the Sun on Earth, thus gaining the appellative “K’inich Ahau” or “Radiant Lords”. In order to elicit this response from a faithful following, hierophanies were employed to evoke the presence of divinity on a temple place or person. Hierophany, (from the Greek roots "ἱερός" (hieros), meaning "sacred" or "holy," and "φαίνειν" (phainein) meaning "to reveal" or "to bring to light") signifies a manifestation of the sacred. When related to architecture, hierophanies may manifest in three ways: A structure may be built in such a manner that from a particular vantage point, the Sun will align either at its setting or rising. These events can be dramatic as they can be witnessed by multitudes. An example of this is the rising Sun seen piercing the central doorway of the Temple of the seven dolls at Dzibilchaltun on the equinox.

A second hierophany is manifested as shadow and light that is cast upon the structure or spaces directly associated to the temple. The most famous of these hierophanies is the projection of triangular shadows upon the Castillo at Chichen Itza. This event is also of a public nature, and today, crowds throng the main plaza eagerly waiting what is now popularly known as the descent of Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent.

A third and more subtle hierophany exists when sunlight pierces the interior of architecture and illuminates the interior in such a way as to define or make more significant a part of the interior design or a person or object that occupies the space.

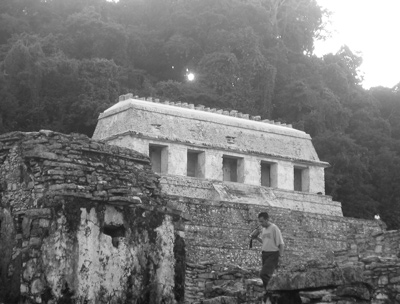

Temple of the Inscriptions, Winter Solstice Sunset. Image Credit: Alonso Mendez

Two major solsticial hierophanies are incorporated into the design of the Temple of the Inscriptions. This temple dominates the central plaza at Palenque and houses the remains of the great ruler K’inich Ja’nahb Pakal. Born on 23 March 603 AD, his accession at the age of 13 marked one of the most significant growth spurts in Palenque’s history. His long reign, perhaps the longest of any ruler, is equally brilliant. At the extraordinary age of 81 years, he was finally laid to rest in a beautifully sculpted tomb deep in the heart of the massive temple. Within the design of this tomb, the message of the divine Sun kings was clear.

Despite the overgrown forest behind the Temple of the Inscriptions, this alignment is still visible when standing at the doorway of House E in the Palace. One can still witness the setting Sun of the winter solstice descend directly behind the Temple of the Inscriptions. The two temples that were primary to the life of Pakal, House E, was built to commemorate his coronation and the Temple of the Inscriptions, the place of his burial. Linda Schele was the first to propose that this alignment might refer to the metaphorical descent of Pakal into the underworld. Winter solstice was seen as having a strong association to death and the weak Sun. Built onto the terraced base of the great mountain that rose directly behind it, the Temple dominated the southern side of the ceremonial plaza and functioned as the portal into the underworld. To corroborate this idea, we discover that the temple was dedicated on December 21, 688 AD-- a winter solstice--favoring the quality of a funerary monument.

At the other extreme, the Sun of the summer solstice came to symbolize the youthful Sun, a powerful force rising from the center of the palace. Though the Temple of Inscriptions is clearly associated to winter solstice, there is also a summer solstice hierophany that is incorporated as a defining element of its design. An appropriate image of the cyclical quality of nature that is in tune with the solar stations is one offered by Loren Eiseley:

Beneath the midsummer sunlight of another year a molecular alarm will sound in the coffin at rest in that silent chamber; the sarcophagus will split. In the depth of the tomb a great yellow and black Sphex will appear. The clock in its body will tell it to hasten up the passage to the surface.

On that brief journey the wasp may well trip over the body of its own mother -- if this was her last burrow -- a tomb for life and a tomb for death. Here the generations do not recognize each other; it remains only to tear open the doorway and rush upward into the sun. The dead past, its husks. its withered wings are cast aside, scrambled over, in the frantic moment of resurrection [All the Strange Hours. 1975].

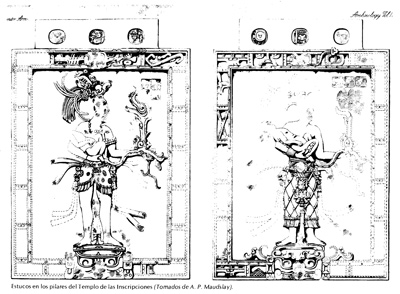

Temple of the Inscriptions Stucco Piers. Drawing by A. Hunter, after A.P. Maudslay

Today through epigraphic understanding, we know that the Temple of Inscriptions along with its importance as a funerary monument, also celebrates the heir presentation of Pakal’s first born son, Kan Bah’lam. This important pre-accession event is recorded as occurring on 17 June 641 AD. This ceremony culminated five days later on 23 June. The passage of divine lineage demanded that as one ruler faded a new one rose with all the elements of a Divine Lord. This message is clear as it is displayed on the facade of the temple piers, where a series of stucco panels portrays the youthful figure held in the arms of both parents as well as grandparents. Shown as literally sprouting or standing on the sacred mountain, these figures present the heir to the grand plaza. This dialogue between solsticial extremes points to a concerted effort by the ruling elite to identify the youthful heir as a transitional figure that is linked to agricultural cycles and the role of ruler as the embodiment of the Corn God. Like an Eiseley wasp, sprouting through the shells of its parents, the young ruler is likened to the cyclical process of Lowland Maya agriculture.

For the lowland Maya of the Palenque region, the corn cycle began on the first Zenith passage and ended on the second Zenith. (Early May- early August) The midpoint of this three-month cycle places us directly on the summer solstice. At this time if one were to visit a milpa, the corn plants typically would stand at just about the height of a human, the stalks would be showing the first little cobs and silks and the plants would also be flowering. Pollination is taking place, and the developing kernels on the cobs are becoming viable. The metaphorical and symbolic associations are powerful for a ruling elite that depended on the fusion of a political and religious governing system to manage resources.

Summer Solstice Heirophany, Temple of the Inscriptions. Image Credit: C. Powell

Cyclical manifestations of the Corn God through divine lineage dictate that the rulers behave like the Sun. Solar cycles are keyed to critical natural phenomenon like the cycle of corn, which in turn help to organize both agricultural cycles and religious celebrations. Association to these grand celestial events enhances the divine ruler’s ability to proclaim his importance as a pivotal figure, and that the passage of divine rulership thus is seen as inevitable as the passage of time itself. In order to fabricate this illusion, city planning conforms to important solar cycles, and becomes the stage for the ruler's drama. These inspiring events called hierophany allowed the ceremonial centers to function as solar calendars that marked the meter of seasonal changes.

2583