Science

We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress, we must recognize our ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty — some most unsure, some nearly sure, but none absolutely certain.

-Richard Feynman

Maya official from the town of Oxchuc, Chiapas, attired in traditional dress from his town, observes the Sun through a special telescope. (Image credit: Igor Ruderman, UC Berkeley)

You hear the word science used often these days. But, what do we mean when we talk about science, and in the context of Calendar in the Sky, what do we mean when we talk about NASA science or Maya science? The word science is derived from the Latin word, scientia, generally meaning knowledge or a system of knowledge. That’s a pretty broad definition! The common use of the word science in modern settings refers to a specific system of knowledge—and the seeking of that knowledge—that has evolved over the centuries and grown out of traditions originating in Europe and the Middle East. In the past century, this modern idea of science became a global endeavor that has pushed the boundaries of knowledge to the very edge of the Universe itself.

Modern science is such a diverse and varied enterprise that it is very difficult to define it in a simple way. In school, we often learn about “the scientific method” that prescribes a scheme for doing science that includes defining a question, forming an explanation (hypothesis), doing an experiment and interpreting the data. But ask any scientist if that is how they do science and you will be hard-pressed to find anyone who answers, “yes.” All scientific endeavors include elements of this method, but the exact process depends on what is being studied. At various times, science can include observation, description, experimentation, prediction, explanation, and more. Scientists tend to specialize in particular areas of science. Few, if any, scientists are engaged in all areas of science. Therefore, different branches of science often differ in what kinds of methods they use.

Science does have several underlying philosophies. The chief idea is that there is an order to nature and the Universe is therefore ultimately knowable. Nature is there for anyone to observe, and anyone can learn how it all works. In this ideal view of science, there are no authorities to dictate the answers.

Another important feature is the concept of objectivity. This is the idea that nature is what it is, regardless of who is observing it. However, we know very well that the perceptions of any observer are influenced by their perspective, emotional state, culture, and so on. So a scientist must make a conscious effort to be aware of and attempt to correct for their own biases. In addition, any knowledge found through science must be confirmed by others, independently of each other, in order for that knowledge to be considered objectively valid. This is why open and honest communication between scientists is essential.

Science requires physical evidence for everything. Observations or explanations of a natural phenomenon should be quantitative—expressible as a quantity—whenever possible. Likewise, scientific reasoning should be logical: every link in the chain of reasoning must follow from the previous link. A scientist should be skeptical whenever evidence is lacking or the logic is weak.

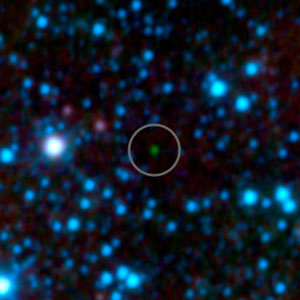

Based on theories of how stars form, a class of very cold brown dwarf stars was predicted to exist. Because they are so cold they have been difficult to observe. But the WISE mission recently discovered many of these very cool stars, confirming the prediction. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/WISE Team)

Perhaps the greatest power of science is that it can accurately predict future outcomes based on its methodical understandings of natural phenomena. For example, if we claim to understand how various forces influence the motions of planets in the Solar System, then we must be able to accurately predict their positions in the future. Predictions should be testable, at least in principle. It’s not very useful to predict something that nobody can ever observe.

Any understanding we have of nature is only an approximation of reality. As time goes on, we expect to learn new things with new tools that will get us closer to understanding reality. Science is self-correcting in this way. It is important that we not become too attached to certain ideas, because new information may come along and change everything.

So, did the ancient Maya practice science? Yes. Their way of gathering knowledge of the natural world was not so different from other cultures. It didn’t have all the features of modern science, but then neither did the science of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Arabians, or Chinese. Science is a cumulative endeavor, and modern science always stands on the shoulders of ancient science. The Maya discovered medicines in local plants, experimented in chemistry to produce ceramics and pigments that have not been replicated. They discovered the various motions and periods of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars allowing them to construct accurate calendars and predict seasons and eclipses. They invented a system of math utilizing the concept of zero, which allowed them to calculate large numbers, long before their counterparts in the Europe, Africa, and Asia. They also accomplished civic engineering feats to rival those of any other civilization in the ancient world.

At Uxmal, Mexico, a tapered stone marker in front of the Pyramid of the Magician casts a minimum shadow when the Sun reaches the zenith—the point directly overhead. This happens only twice a year, and the first zenith passage correlates with the onset of the rainy season. (Image credit: Bryan Mendez, UC Berkeley)

The Maya people of today use both modern and surviving traditional knowledge of astronomy, mathematics, use of medicinal plants, and other scientific knowledge that they apply for agriculture and for the health and balance of their communities. Many of the practices of modern science, like observation, measurement, record keeping, analysis of evidence, etc. have been practiced by the Maya for thousands of years.

When we speak of NASA science in Calendar in the Sky, we are talking about that modern endeavor of science that we learn about in school. When we speak of Maya science, we are speaking about the way the ancient Maya investigated and came to understand their world. They are not the same, but they share the same goal of understanding the Cosmos in which we all live.

1261